Chris Kelso was kind enough to share his essay/interview with Buddy Giovinazzo author of Life is Hot in Cracktown and writer/director of the Troma film Combat Shock. Chris is also starting a new press along with Nicholas Day. It’s called ROOSTERVISION, and it’s all about film studies, so if you have

Opening Scene –

I used to nourish myself on a strict diet of late night trash TV…

A loan soldier appears, weaving in and out of the ricefields of Da Nang; an infantry rifle clutched to his chest. My innocent eyes fastened to the screen. My knees were a little numb from leaning on them with my elbows for so long. Parents in bed, resting like bodies. The soldier with lank black hair is sweat-slicked, muddy, and terrified – I would soon discover that this was Frankie, our titular hero (or anti-hero). Something about his face hits me in the base of my gut, it’s a face I recognise. Tortured, hopeless, raked of something vital.

Images of Frankie then become interspersed with archival stock footage of the Napalm bombings, the only thing missing is ‘Ride of the

My dad woke up, came into the living room and yelled at me just as Mike the starving junky started to open up a septic abscess in his arm with the end of a coat hanger so he could tap a vein. That was a

It’s funny, he actually remembers the whole incident. I think the extreme impact of Mike the junky seared itself onto his mind’s eye. So ‘Combat Shock’ even made a cursory impression on my dad, who is a rather robust character from provincial Ayrshire, all calluses and brawn.

Another thing about this movie was that it was so low budget, but my infantile brain got so wrapped up in the sense of dread, I barely even noticed. You should believe me when I tell you that

Then we’re in a run-down Staten Island apartment potted next to an active railroad. Frankie’s life is arguably worse now he’s out of the VC. The harsh, Kafkaesque jungle of 80’s NYC is a different existence entirely. Frankie is unemployable, unskilled and lives a truly bleak reality. His depressed wife nags him every day and the constant rumbling of passing trains is interrupted only by his deformed child, Rikki’s, awful yowling – presumably a result of Agent Orange poisoning. Everything has gone wrong. His toilet is broken, the milk is sour, and his Converse are busted. The family are ‘living like rats’.

We get a sense that it’s all building up to some awful conclusion, something Hubert Selby would’ve concocted in the delirious heights of his Streptomycin treatment – the whistling kettle and dripping tap are a bass intro to some great impending final chorus of agony. Frankie soon learns he is to be evicted.

Ricky Giovinazzo’s soundtrack is another major character in the movie. In the opening scenes, he musters a score so apocalyptic and epic your heart will thud in your ears. You’ll be praying for it all to end and yet it feels like Frankie’s torture could never end, in this life or the next. This is a stark contrast to the ominous synth, the quiet after the bombs have dropped, measured, deliberate.

There are a number of things that make ‘Combat Shock’ such a standout – not least Giovinazzo’s remorseless cynicism. I was the most depressive young man – even before I was a teenager I was quiet and obsessed with dark things. This movie provided some

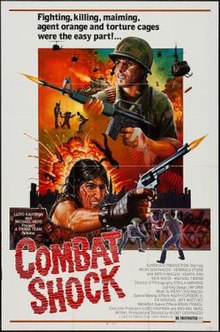

Giovinazzo himself describes this film as a cross between ‘Eraserhead’ and ‘Taxi Driver’ and these are fair comparisons, but before I’d seen either of those movies, ‘Combat Shock’ struck me on a primal level and in a profound and terrifying way it helped shape who I would become as an adult. This was a darkness that was relatable. I’d never seen anything like it before.

What makes Combat Shock such a Troma aberration, aside from its mature tone, subject matter and unyielding straight face throughout, is its subtlety. This might sound strange for a

“The terror is real, it’s part of me now and I can’t escape it…” The nightmare of war.

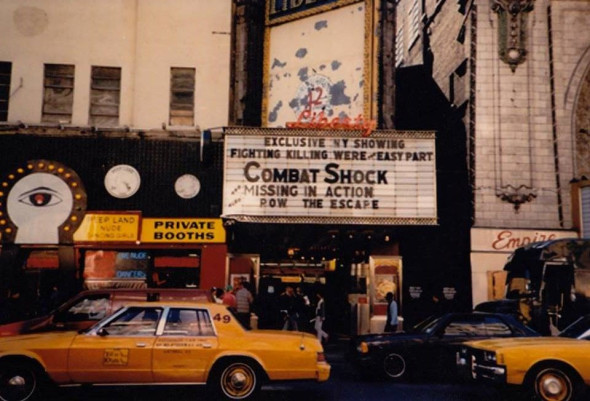

‘Combat Sock’ originally appeared on the festival circuit under the title American Nightmares. Of course, the MPAA had objections…

I hunted down Buddy Giovinazzo. He sent me his direct number and I called him in Berlin. I was nervous as fuck…

CK – Sorry if I sound nervous, sorry about my accent.

BG – Don’t apologize. I got a thick New York accent…

CK – You sound all romantic, like Woody Allen. But thank you for being so kind.

BG – Thank YOU. I’m pretty stoked you guys are so into ‘Combat Shock’ in the UK.

CK – You should definitely come to Glasgow

BG – We actually came up to Scotland, to Edinburgh and wound up staying for a few days because we liked it so much.

CK – Did you go to the Fringe festival?

BG – No, it was called the FAB, the FabFilm Fest. We just had a great time and were during the big ash cloud, about six years ago. All the stores were selling gas

CK – That’s pretty cool

BG – Yeah, I think it was in Iceland or something at the time and was affecting all surrounding countries.

CK – I think we get all the shit from surrounding countries. I think it had something to do with an eruption of a sub-glacial volcano or something.

BG – Yeah, it was crazy

CK – If you have any intention of coming back over let me know.

BG – I absolutely will. We’ve just been in LA for three months so we’ll be chilling out in Berlin for the next year, but maybe after…

CK – Were you working in LA?

BG – Yeah, I was there for a show. We go, my wife and I, back every year for a few months.

If you read his books or watch any of Giovinazzo’s movies, you’ll become instantly aware that the worlds and characters he smears across your brain are so utterly void of light or hope, the velveteen darkness feels like the only place to be, the only place of mercy. I can relate to this. This movie demands that its audience accept the film on its own terms. The screaming innocents as deafening as the whistling of a falling Daisy Cutter – you better be ready for the unrelenting conflict that’s about to unfurl before your very eyes, because once you’ve seen it, you cannot un-see it.

CK – I meant to ask, how did you end up in Berlin? Relocating from New York to Eastern Europe must’ve been quite a shift?

BG – I was actually living in LA before I came to Berlin, so I initially moved from New York to LA. I was in LA for three years before moving here to Berlin. I pretty much moved here because I couldn’t afford to stay where I was. I mean I wasn’t working. After I did my second feature ‘No Way Home’ I couldn’t get any work for three years. Things were getting worse and worse financially and I was in major fucking debt so I had a chance to come to Berlin and live for free for a few months and I figured I had to do this because I couldn’t stay where I was anymore. So I figured I’d come to Berlin for a few months then go back to LA and re-start my career. But once I got to Berlin I fell in love with the city, I mean I was completely at home here – even though I didn’t speak any German and I didn’t know anybody it was really like New York for me, ya know, the New York of my childhood. Then I got a call from a German company who said, ya know, ‘we hear you’re living in Berlin. Why don’t you work for us?’ It turns out my second feature was actually very successful in Germany. They knew of it. So I decided to stay. I was happy here. When I realized I could work here I said ‘fuck it, I’m gonna stay.’ And I did.

CK – I know you’ve been working on Leipzig Homicide.

BG – Yeah, I basically work on German TV movies that play on Sunday nights. That’s how I live, that’s how I finance my independent film career.

CK – Do you still get to be creative? Is it satisfying creatively, emotionally, spiritually?

BG – It’s not as good as writing and directing your own material. I’m basically just a director over here. I do like directing something I didn’t write though, it means I get to do

CK – It’s weird because the first time I came across your work it was the novel Potsdamer Platz, which was a sort of

BG – Yeah

CK – Was it close to becoming a movie?

BG – Yeah it was fucking close. Tony Scott bought the rights in 2000 and right up until his death kept buying the rights every year. He was always going to direct it but every time it got close he’d be offered a bigger film. One that paid him more money. So we came close, maybe three or four times to really almost getting it made. It never happened though. He was a great guy and he really loved the book. I would’ve loved

(Pause to close window for hailstorm that has swept through Berlin)

CK – I downloaded this recorder APP for my phone and it only records in five-minute increments, which is really annoying. So every five minutes I have to restart the device. So I’m going to have a hell of

BG – Shit man, that is annoying.

CK – My fault for not being better prepared or having a Dictaphone. So, let’s talk about Combat Shock which is a film that really fucked me up as a boy in his mid-teens. The part of Scotland I’m from is pretty hellish. The West of Scotland is tough. I’m originally from a place called Cumnock which recently had the inauspicious accolade of being ‘Britain’s worst town’ – so there’s an idea of what kind of place we’re dealing with here. My mum and dad were really protective of me growing up and I didn’t get to leave the house very much so I was pretty sheltered. But I remember Combat Shock was on TV, on channel 4, you used to get quite interesting films on channel 4 at night – and it was like 10 minutes before Mike the drug addict is using a coat hanger to open up a septic arm wound. It was absolutely horrifying and obviously the scene at the end with the baby. It was so relentlessly bleak. It was horrifying but kind of instantly relatable. I was quite a morbid teenager and have become a fairly morbid adult so it really appealed to my sensibilities but still, I think that scene and the scene from Alien where the chest-burster erupts from John Hurt’s chest are two images that have burned themselves on my psyche. I wasn’t very age appropriate to see those things but they really stayed with me and actually informed the way I wrote in my early novels. Then obviously I read ‘Life’s Hot in Cracktown’ and realised you were a master of all forms.

BG – That’s how I feel about it too. Have you seen the movie Life’s Hot in Cracktown?

CK – No, just the book, but I thought it had tremendous literary merit.

BG – Thank you. The DVD’s pretty hard to get a hold of. The film takes place all at once so it’s more harrowing than the book. The film is basically five stories out of the book, I had to narrow it down. They take place at the same timeframe. So it cuts from gangs to prostitutes to kids in the hotel and cuts back and forth, then it all

CK – Cool. I imagine the book is quite difficult to film because the book is such a literary experience. There are elements of rap and street poetry and there’s a focus on the prose and how it’s written. The film will obviously be much more visceral from an imagery standpoint. I’ll buy it when I get paid next I promise.

BG – I’ll hold you to that sir.

CK – I actually contacted you quite a while ago and I don’t think you replied. Or I figured maybe he’s too busy or that’s quite an unprofessional way to contact someone.

(Buddy talks to someone out of earshot)

BG –Sorry I’m just talkin’ to my wife, said I’d call her back. She’s in Hamburg.

CK – Is your wife German?

BG – Yeah, she is. The only German woman in Germany.

CK – I know that the re-issue of the DVD has a lot of great special features and the commentary is interesting but I’m quite poor so it makes sense for me to just call you and ask you yourself. How did you wind up casting your brother Rick in the movie? I understand he’s primarily a musician?

BG – My brother is a very shy guy who’s never acted before or since. I think we should try and get him to speak about his role. He saw the screen-test on super 8 and he said he was better than all of them. So I cast him. I needed someone for two years because I knew I didn’t have the money to do it quickly. He turned out to be perfect. He’s really sympathetic. I don’t think Mike the junky would’ve been as sympathetic, I was going to cast that actor the first time. There are four short films I did before combat Shock and I cast Mike the junky in all of them. He’s a film professor in North Carolina and still makes low budget features. He’s a good guy.

[It’s difficult for Giovinazzo to find an American or British publisher because his work is very dark – which I find curious given my own work is wilfully depressing and dark and I’ve never struggled to find a distributor, even though my work is inferior to

Giovinazzo delivered a true Troma masterpiece – but not just that, a true snapshot of Reagan’s America and a deserving entry into the Vietnam War cannon. “I go back there every night,” Frankie tells us, and our guts churn at the prospect of a human being revisiting such an awful memory during sleep. Giovinazzo’s frightening vision almost didn’t make it to the screen.

[One of the gaffers on Combat Shock who worked on Splatter University with Troma told him to try Troma. In fact, Buddy thought the movie had initially been rejected by Troma (a director with the company said Kauffmann had watched the movie and didn’t like it). He tried to sell the movie elsewhere for a year and strained to get it in film festivals. Never to be put down without a fight, Giovinazzo called Troma headquarters personally and asked to speak to Kaufmann himself. He asked Lloyd to reconsider the movie. Kaufmann claimed never to have seen the film. A day later they called Giovinazzo back and said they were in love with the movie and that they’d be

CK – The director who told you the movie hadn’t interested Kauffmann sounds like a cunt.

BG –Yeah he was, I think he was jealous. They re-screened the movie and bought it right away.

CK – How long was it between ‘Combat Shock’ and ‘No Way Home?’

BG – Combat Shock really hurt me. It wasn’t liked by anybody for years. People who watched it thought they were going to see an action movie because there were posters advertising it as the next Rambo movie. There’s no gang fights or battle footage. So it took 3 or 4 years in the horror genre to find it. I’d be up for jobs and when they asked to see my first feature they’d look at Combat Shock and they wouldn’t want to work with me. It’s not a genre film to them. It’s a genre film now.

CK – Is that when you started writing novels during this hiatus?

BG – Yeah I started writing novels because I couldn’t get any film work. I was frustrated. I knew that any time I wrote a script I needed a ton of money to get it made so I’d have to find someone to give me money and I just found that impossible to do. So I started writing books because when they’re finished they’re finished and you just a find a publisher. You have much more creative freedom writing a book. So I wrote ‘Life’s Hot in Cracktown’ and I guess I got it published in 1991.

CK –Without kissing your arse, your novels are excellent. You transition from screenwriter to novelist was seamless.

BG –Well thank you. Screenwriting involves a lot of reading. I remember reading Jim Thompson a lot and after a while, I said I could write a book like this. Jim Thompson’s stuff wasn’t overly complicated, he was writing about criminals and the underworld. That’s a world I love so I just started writing stuff like that. But, as you said earlier I could never make a living writing. It’ll take me a year or four years to write a book and you only earn like a few thousand dollars and you can’t live on that.

CK – But during the actual production, did you have assistant directors or anything to kind of guide you? Or were you thrown in the deep

BG – I had

CK – So what would you have changed? Can you watch it again and still be happy with it?

BG – I’m the

CK – I only reali

BG –Yeah, I just came in for a short hello.

CK – So what kind of difficulties did you face? Was it a tense set? What was the atmosphere? Was it just a kind of giddy excitement because everyone really believed in the project? I imagine it would be pretty terrifying?

BG – Nah, it was fun. It was totally not tense. We didn’t have a schedule, there wasn’t any money involved, we weren’t paying people, and there was no overtime. In that way, it was like making a student movie. Having total and complete freedom to work with your friends, with people you like. Part of the problem is that some of your friends aren’t so talented. So there are many mistakes and you can’t complain cos you’re not paying anyone. But it was exhausting because

CK – I know you did a segment of Theatre of the Bizarre – so when you work now, or even when you worked on ‘No Way Home’ with Tim Roth, was that much more of a professional set-up? Did you have Assistant directors at your disposal or was it still pretty much just you doing everything?

BG – No. ‘No Way Home’ was a real film with a real crew. We had maybe 40 people, we had everything that I never had on Combat Shock. That was real. I had producers, production designer, I had a good camera person. So that was a real movie. In spite of that, we were still very loose on set, we were able to change things, we were able to improvise. I worked very loose with actors. Something will happen on set and I’ll say that’s a better idea than what we had planned so let’s shoot that instead. Same thing with the Theatre of the Bizarre. It was really low budget, no one got paid, but it was also a real film and a real crew. We had enough people to do everything we needed to do.

CK – So do you ever think about going back

BG – Well, I did that in 2012. I made a low budget horror film for 100,000 dollars called ‘A Night of Nightmares’ that went around some festivals. That, to me, was kind of like doing ‘Combat Shock’. We had 12 shooting days with a small crew and a small cast. I loved it! The problem is you can’t live like that. You wind up doing a film like that and at the end of the film you lose money, you still have to pay to live. You have to

Hey man, I forgot to tell you a story from shooting. The house of Frankie Dunlan, this house we rented downstairs, we shot on the second floor. So we rented it for a month and it was really nice. The landlord had painted it so it was fit for a family, you know. My special effects guy Ralph Cordero, we had to make it look rundown see. So Ralph said he would put latex on the walls, put ink in the latex and make the walls look dirty and grimy then at the end of the shoot we could wipe the latex off, kind of like a rubber. It’ll peel right off. So we did that, we painted every wall, put up really horrible wallpaper, anything to make it look horrible. Then at the end of the shoot we started peeling the latex off, but the walls were disgusting and filthy and we didn’t realize the ink in the latex had seeped into the wall. So all the walls were fucked. We had to re-paint the entire house.

CK –Shit…

BG – Worse than that, in the bedroom where Frankie kills his wife, we used gallons of blood for that scene. So anyway, we spent like a week cleaning up the blood form the bedroom. So I’m out of the house, I’m cutting the film in the editing suite. A week or two after I left the house I get a phone call from the landlord, his name was Artie. He was really hysterical. He told me he was showing the house to a couple. He was showing a family around the house and when he went to show them the bedroom, blood started to seep up out of the wood. I didn’t realize that, of course, wood will absorb any liquid. So the floorboards, even though we cleaned it, the blood came up to the surface. So Artie was screaming at me “What did you do?” So I said to him to relax, it’s not blood. It’s syrup. And I had to prove to him that it wasn’t blood, that we didn’t kill anybody and we shot a movie there. We laughed about it afterwards but…

Buddy feels strongly about his subject matter. He reminds us of

There is an important section of the film when Frankie is accosted by Paco the loan shark and his cronies. We learn that Paco owns everybody. Frankie doesn’t own a single thing in the world. He has

This movie is a fucking endurance test and it’s amazing.

Everyone is operating with surface desire, one goal – to score, to survive, to escape. Even the rabid but loveable junky Mike has resorted to mugging people so he can pay Paco for a hit. The desolate landscape is interspersed with flashbacks of Frankie in a VC torture cage.

War is the annihilation of everything that is beautiful. Giovinazzo, while presenting an undeniably cynical film, does offer us the hypothesis that war is not natural to man, that it is the antithesis of our need to be free and exult in a sense of community.

Early on, Frankie is stalked by armed natives, one of whom is a beautiful woman. He initially basks in her beauty, even when confronted with a conflict scenario. In the end, his fear is the destroyer and Frankie reverts to fight or flight. He turns around and shoots the beautiful girl. He lowers his gun and watches the slow-motion slump of his target. Frankie is so disgusted by his actions he drops his gun and runs off through a graveyard of his murdered comrades.

“I’m a hero. God help me!”

This post may contain affiliate links. Further details, including how this supports the bizarro community, may be found on our disclosure page.